Built Environment

by Sadiq Toffa

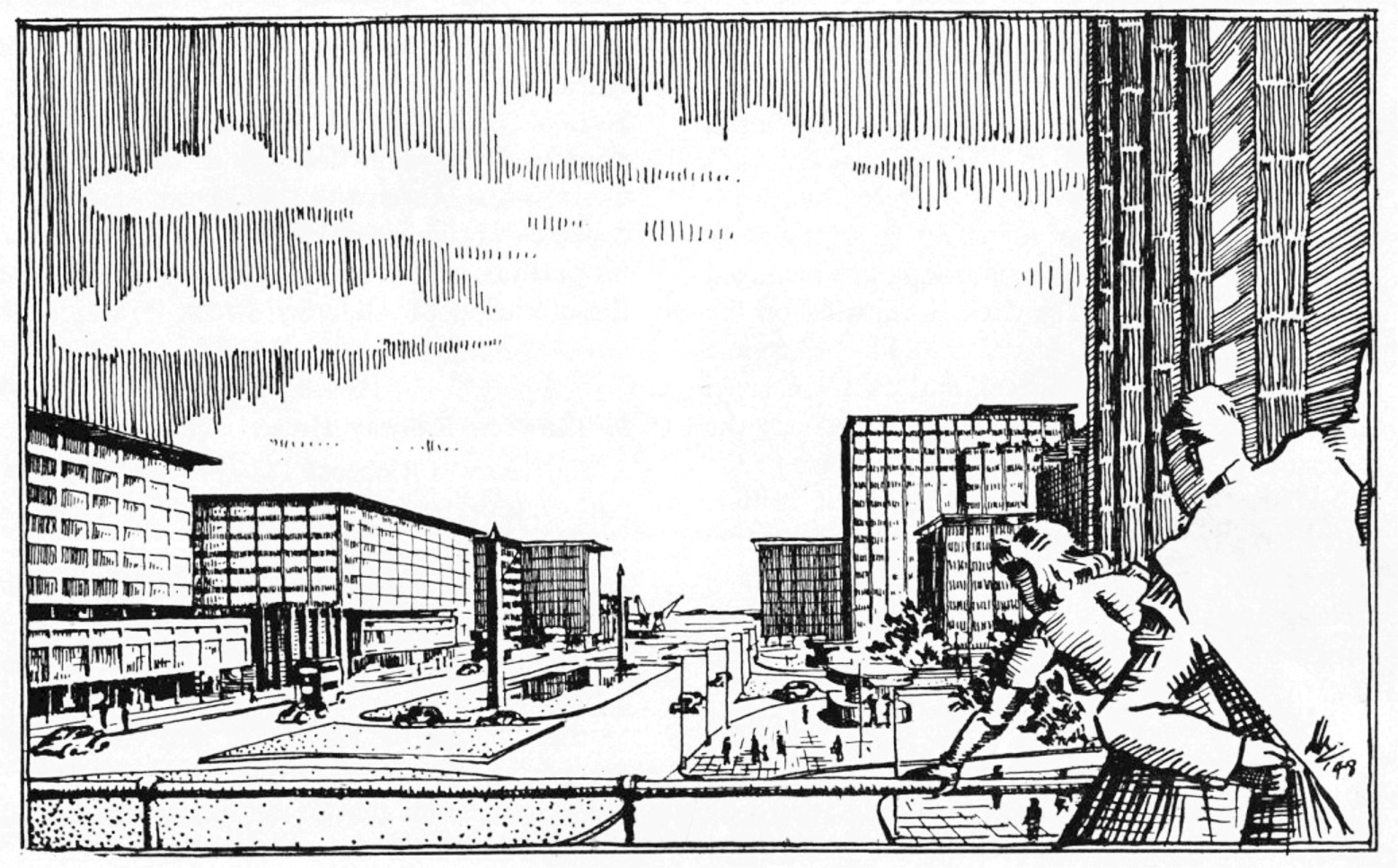

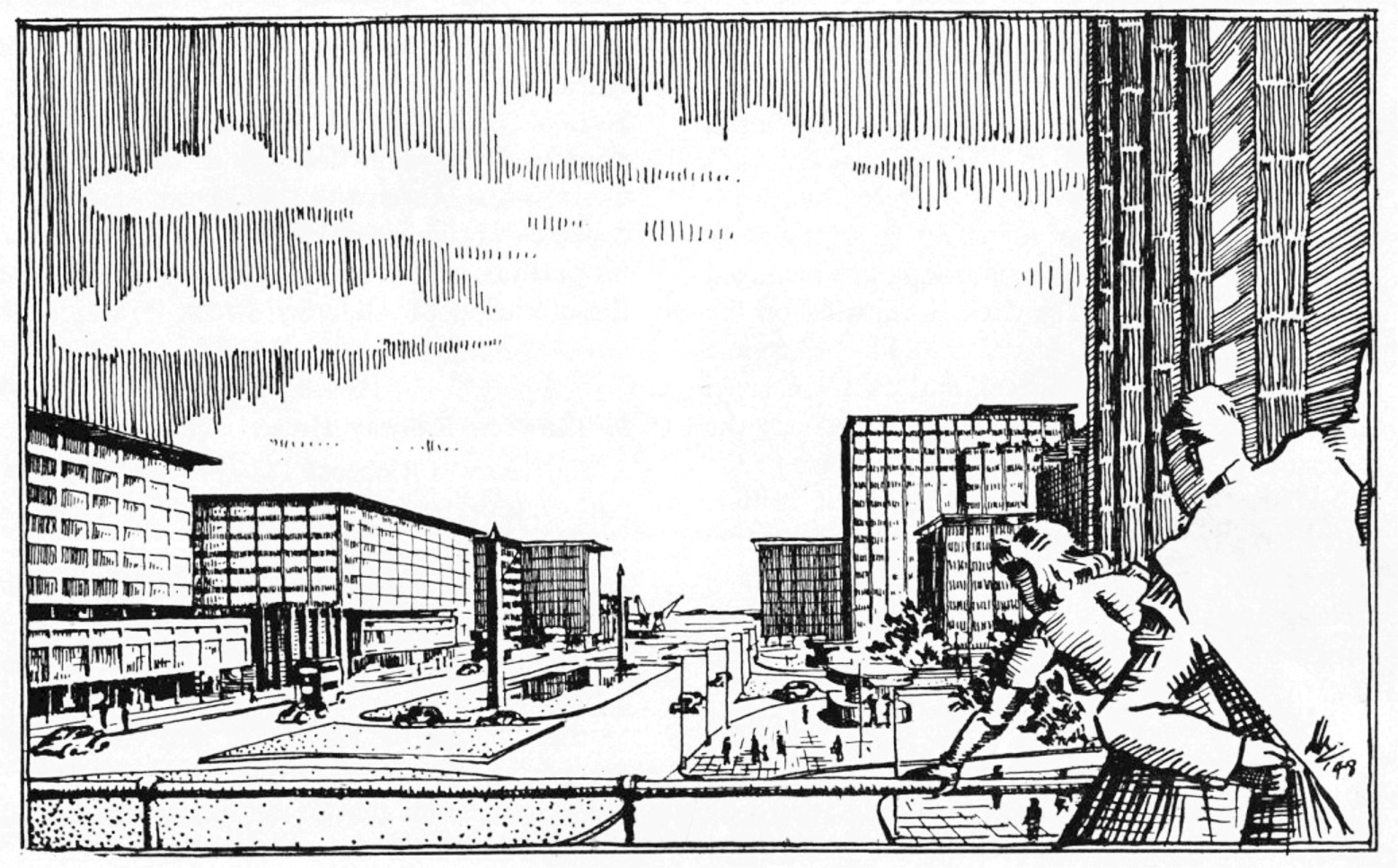

The Slums Act of 1934 and the Health Act of 1935 had a major impact on the Bo-Kaap over the next 50 years. They envisaged the elimination of racially mixed “slums” and the development of the Cape Flats townships. Through a major foreshore development and new transportation system, a wholly segregated and modernist central city would be created.

Although the Buitengracht freeway never constructed, buildings were demolished in preparation for its construction, and parking garages and workshops were built on its periphery as “servant spaces” for the anticipated infrastructure.

Under the Group Areas Act of 1950, the Bo-Kaap was divided into two sections: a “Malay Group Area”, for Muslims, and a “Coloured Group Area” for non-Muslims. In addition to religious and geographical differences, Apartheid ideology also constructed class differences between the two groups.

The restoration of the Malay Group Area by the City Council in the 1970s would censor the diversity of the Bo-Kaap’s architecture and culture, to produce a single romantic image of the Malay community as representing a Dutch past.

The colourful houses, that fascinates visitors today dates from this restoration period onwards. It is particularly related to the recognition of domestic dignifying and celebratory aspects of Ramadan and Eid. Colour is therefore both symbols of an orientalist vision imposed on the community, but also of individual and group dignity, pride, and identity.

Ramadan cookie-runs and house painting in preparation for the sacred day of Eid-ul-Fitr